ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

December 20, 2020 to October 24, 2021 | Level 3

Silk cloth is associated with wealth and status throughout the world but few may realize this rare, natural fiber is indigenous to sub-Saharan Africa. Silk was traded between African peoples across the continent and was also imported from Europe, India, China, and the Middle East. This installation of cloths drawn from the DMA collection explores the production of silk and silk textiles in Ghana, Nigeria, and Madagascar.

VIRTUAL TOUR

SILK IN AFRICA

SANYAN SILK (or wild silk) is produced by Anaphe and Epanaphe silk moths. Native to sub-Saharan Africa, these moths dine on tamarind trees.

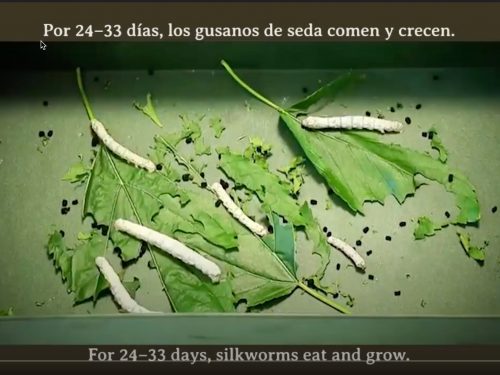

MULBERRY SILK is produced by Bombyx mori silk moths and is named for the type of tree that sustains the moths.

GHANA

Kente is a popular textile identified with the Asante peoples. Osei Tutu I, the first asantehene (king) reserved the cloth for royals, chiefs, and other notables to wear on ceremonial occasions. Weaving kente began around 1730 with yarn collected by unraveling silk cloth imported as diplomatic gifts or trade. Bonwire, a village in south-central Ghana near the Asante capital, continues to be the cultural center for weaving. Kente is woven on seated horizontal looms and was originally a male profession. Today, with the exception of royal kente, most “silk” cloth is made of rayon and both men and women work as weavers.

NIGERIA

In Nigeria, weaving silk is a male profession practiced among the Hausa and Nupe Muslims in the north and the Yoruba in the south. These groups do not cultivate silk moths; they buy silk cocoons from hunters. Robes like the one hanging nearby are made by Nupe weavers living in Hausa communities. These weavers worked on warp stretch looms—horizontal looms that do not have a frame. The prestigious men’s garments, once symbols of political and religious affiliation, are now worn by Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

Among the Yoruba, handwoven cloth is made with wild silk and used to make ceremonial garments for both men and women. Synthetic yarns have long replaced wild silk, but both are commonly referred to as sanyan (silk).

MADAGASCAR

During the mid- to late 19th century, the Merina kingdom, located in the central highlands of Madagascar, was world-famous for handwoven silk cloth. There was a centuries-long practice of weaving silk produced by indigenous silk moths. The cloth from native moths (not shown in this gallery) was heavy, with a rough texture, and continues to be used to make burial shrouds. During the early 19th century, the kingdom imported Chinese silk moths and mulberry trees (the insect’s habitat and food source). As seen in the adjacent display, this cultivated silk produced luxurious cloths that were soft, smooth, and easily dyed.

Women using ground looms were the exclusive weavers of prestigious lamba akotifahana, shawls with brocaded patterns. The shawls they wove were worn by royals and aristocrats and gifted to foreign diplomats or heads of state.

EXPLORE MORE

i

BEHIND THE SCENES

Take a behind-the-scenes look at the exhibition Moth to Cloth: Silk in Africa with Dr. Roslyn A. Walker, Senior Curator, Arts of Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific/The Margaret McDermott Curator of African Art; Fran Baas, Interim Chief Conservator, and Mary Nicolett, Senior Preparator. Explore the production of silk and silk textiles in Ghana, Nigeria, and Madagascar while reflecting on unique textile conservation and display techniques.

Focused installations allow us to study works from our vast and renowned collection of African art from a variety of interesting angles. We hope ‘Moth to Cloth’ will provide visitors with an opportunity to learn about the cultural significance of these treasured garments and to make discoveries about silk’s long history in Africa.

– Dr. Agustín Arteaga, Eugene McDermott Director, Dallas Museum of Art

A: First, it should be remembered that African silk comes from either wild or domesticated moths. Both types are found in Madagascar. Wild landibé silkmoths (from species of moth from the genus Borocera) produce silk that is naturally earth-toned, strong, and rough-textured compared to that from domesticated mulberry or “China” silkmoths, which is lustrous, smooth, and easy to dye. (Mulberry silkmoths were introduced to Madagascar in the early 19th century from China and feed on white mulberry leaves.) Wild silkmoths belonging to the Anaphe and Epanaphe genera are indigenous to Nigeria where they have not been domesticated. Hunters find the cocoons in the forest and sell them to the textile specialists. The silk produced from these silkmoths is heavier than “China” silk and tends to be dull and textured like homespun cotton. Like “China” silk, all African silks are significant and prestigious because their acquisition is historically beyond the means of ordinary people.

A: First, it should be remembered that African silk comes from either wild or domesticated moths. Both types are found in Madagascar. Wild landibé silkmoths (from species of moth from the genus Borocera) produce silk that is naturally earth-toned, strong, and rough-textured compared to that from domesticated mulberry or “China” silkmoths, which is lustrous, smooth, and easy to dye. (Mulberry silkmoths were introduced to Madagascar in the early 19th century from China and feed on white mulberry leaves.) Wild silkmoths belonging to the Anaphe and Epanaphe genera are indigenous to Nigeria where they have not been domesticated. Hunters find the cocoons in the forest and sell them to the textile specialists. The silk produced from these silkmoths is heavier than “China” silk and tends to be dull and textured like homespun cotton. Like “China” silk, all African silks are significant and prestigious because their acquisition is historically beyond the means of ordinary people. A: The historic trans-Saharan, coastal, and internal trade routes brought new products, materials, technologies, new religions, and ideas from the world beyond continental Africa. The exchange was mutually beneficial but also detrimental to Africa, e.g., the trans- Atlantic slave trade and colonialism. Among Africa’s many cultural contributions are the various textile patterns, including those produced in silk, which for more than a century have long inspired Western designers of haute couture and home furnishings.

A: The historic trans-Saharan, coastal, and internal trade routes brought new products, materials, technologies, new religions, and ideas from the world beyond continental Africa. The exchange was mutually beneficial but also detrimental to Africa, e.g., the trans- Atlantic slave trade and colonialism. Among Africa’s many cultural contributions are the various textile patterns, including those produced in silk, which for more than a century have long inspired Western designers of haute couture and home furnishings.